Gold bracelet highlights Australian flora & fauna

attrib. to HOGARTH, ERICHSEN & CO., Australia c.1854-65 (Manufacturer) / Julius Hogarth, Australia 1821-79 (Designer) / Conrad Erichsen, Australia c.1825-1903 (Maker) / Bracelet 1864 / Gold modelled in high relief with rusticated frames. The central section with an emu and brolga separated by a palm tree and subsidiary links depicting snake, kangaroo, possum and lizard / 3.8 x 17 x 1cm / Purchased 1987. QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / View full image

The discovery of gold in the 1850s started a series of rushes that transformed the Australian colonies. In the burgeoning economy of the gold rush period, and with the increasing demand for locally produced metal work — motifs of native birds and animals appeared on colonial jewellery and silver.

Failing to make their fortunes on the goldfields, Julius Hogarth (Hougaard) (1821-79) a sculptor from Denmark and Conrad Erichsen (c.1825-1903) an engraver from Norway — who met on their voyage to Sydney in 1852 — became silversmiths and jewellers in Sydney. Eventually opening their workshop Hogarth, Erichsen & Co., Jewellers and Watchmakers in 1854, they produced presentation pieces for elaborate ceremonies, sporting trophies and jewellery, their specialty incorporating Australian flora and fauna motifs.

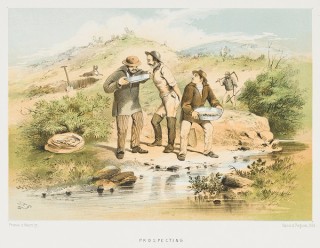

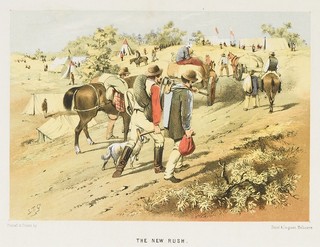

S T (Samuel Thomas) Gill (1818-80) born in England, is best known as the first colonial artist to display a distinctive Australian character in his works. These images from his ‘The Australian sketchbook’ (illustrated) chronicle life on the gold fields and give a glimpse of the hard life where only a few struck it rich.

S T Gill ‘Prospecting’ 1865

S T Gill, England/Australia 1818-80 / Prospecting (from ‘The Australian sketchbook’) 1865 / Colour lithograph on smooth wove paper / 28.9 x 43.3cm / Purchased 1962 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / View full image

S T Gill ‘The new rush’ 1865

S T Gill, England/Australia 1818-80 / The new rush (from ‘The Australian sketchbook’) 1865 / Colour lithograph on smooth wove paper / 28.9 x 43.3cm / Purchased 1962 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / View full image

This gold bracelet is attributed to Hogarth, Erichsen & Co. because of the strong resemblance it bears to a group of massive and beautifully wrought brooches and bracelets made by Hogarth and his partner Erichsen. A description which appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on 9 July 1859 confirms the quality of their workmanship:

‘As truthful illustrations of the natural history and floral beauties of the colony, nothing could be more perfect, the different objects whether quadrupeds, birds, foliage, fruit or flowers being truly lifelike. Never, perhaps in gold at least, has the plumage of the feathered tribes of Australia or the airy lightness of the flowers and ferns been displayed to such advantage, as in these chefs d’ouvre of art. [a masterpiece especially in art]’

Bracelet 1864

attrib. to HOGARTH, ERICHSEN & CO., Australia c.1854-65 (Manufacturer) / Julius Hogarth, Australia 1821-79 (Designer) / Conrad Erichsen, Australia c.1825-1903 (Maker) / Bracelet 1864 / Gold modelled in high relief with rusticated frames. The central section with an emu and brolga separated by a palm tree and subsidiary links depicting snake, kangaroo, possum and lizard / 3.8 x 17 x 1cm / Purchased 1987. QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / View full image

The rusticated borders and detail of the bracelet are similar in style to other bracelets which are also attributed to these makers in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney and National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and is consistent with the bracelet’s presentation date engraved on the clasp.

This bracelet is of special significance as the emu is paired with a brolga (illustrated) instead of its usual partner, the kangaroo as seen in the coat of arms of Australia (granted by King Edward VII in 1908). Brolgas can be found across tropical northern Australia, throughout Queensland along the coast from Rockhampton to the Gulf of Carpentaria and in parts of western Victoria, central NSW and south-east South Australia.

(left) Bracelet 1864, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / (Right) Bracelet 1858, Collection: Powerhouse Museum, Sydney / View full image

Curatorial extracts, research and supplementary material compiled by Elliott Murray, Senior Digital Marketing Officer, QAGOMA

Bracelet 1864 is on display within the Queensland Art Gallery’s Australian Art Collection, Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Galleries (10-13).