Fairy Tales: The history & hidden meaning of ‘Beauty and the Beast’

Bill Condon (director), United States; Sarah Greenwood (designer), England / From Beauty and the Beast 2017; Cast: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Luke Evans / / ‘Rose in a bell jar’; Glass, plastic, wire; 61 x 36 x 36cm / ‘Mirror’; Mirror, plastic, paint; 45.7 x 21.6 x 5cm / ‘Table’; Wood, marble, artificial snow, resin, plastic; 76.2 x 101.6 x 101.6cm / Courtesy: The Walt Disney Company / © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved / Photograph: N Umek © QAGOMA / View full image

Transformation is an essential element in the fairy tale tradition. A change of appearance can signal or conceal a character’s true identity. While some characters alter their own appearance to escape or trick others, many are victims — transfigured as punishment. The spells that trigger these transformations are, in many cases, broken by a character’s moral redemption, or the compassion of another who sees beyond their altered appearance.

Talk | 10.30am Sunday 14 April

The story of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ has captured imaginations for millennia. Free at the Australian Cinémathèque, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) at 10.30am on Sunday 14 April we will be joined by the award-winning author, poet, and performance storyteller, Dr Kate Forsyth, for a fascinating talk delving into the rich history of this ancient tale in A Tale as Old as Time: The History and Hidden Meaning of ‘Beauty and the Beast’.

Book signing

At 11.30am in the GOMA Cinema Foyer, join us for a book signing of Kate Forsyth’s Long-Lost Fairy-Tales. Illustrated by Lorena Carrington, this new book available for purchase from the QAGOMA Store, is a selection of twenty-one little known wonder tales from around the world, brought back to life for the modern-day reader.

Dr Kate Forsyth / View full image

We asked Kate Forsyth about the importance of fairy tales in her writing.

Sophie Hopmeier / As an author of fiction, how have fairy tales influenced your writing?

Kate Forsyth / I’ve always loved fairy tales and myth, and I’ve always loved writing, so the two things have always been linked for me. My very earliest stories were filled with adventure and magic and mystery, and a kind of fairy tale atmosphere — a place where anything can happen. All of my books are very different, however. Some draw on fairy tales and myth explicitly, and others just carry faint echoes.

Sophie Hopmeier / As well as being a writer, you are also a master storyteller. What different qualities are brought out in stories when they are written or spoken?

Kate Forsyth / When I am adapting an old folktale for a live performance, I’m concentrating on reducing the tale down to its simplest and purest form, revealing the pattern of action within. All my stories are performed from memory, and so I need to create an interlinked chain of vivid images and phrases that help me remember which narrative component goes where. Poetic devices such as rhythm, rhyme and repetition are useful mnemonics and work so well in a live storytelling performance.

When I am drawing on a fairy tale in a novel, I am doing the opposite. I am expanding the story, developing a rich, complex world populated by multi-dimensional characters, and I am hiding the pattern of action within a woven web of action, dialogue and description. The fairy tale is a shadow story within my narrative, adding depth and symbolic meaning, and helping the reader make connections to wider themes.

Sophie Hopmeier / In your upcoming lecture you will be speaking about the history of ‘Beauty and the Beast’. What is it about this story which particularly fascinates you? Do you have a favourite version?

Kate Forsyth / ‘Beauty and the Beast’ has always been one of my favourite tales, but I have no idea why! I think it’s because it’s a story about a girl who was brave enough to face a monster and find the humanity within. It’s about seeking to understand what has been hidden, and about the importance of courage and compassion. I also like the way the girl must be strong and steadfast in her refusal, despite her terror of the Beast, and the fact that she goes to the Beast’s castle to save her father. I have a few favourite versions. The first is the myth of Eros and Psykhe, said to be the prototype for all the other versions. Psykhe must travel to the underworld and face the queen of the dead to save her beloved, which adds a greater dimension of peril and darkness to the tale. I also love ‘East of the Sun, West of the Moon’, in which the beast-husband is a white bear and lives in a castle of ice and snow, ‘The Singing, Springing Lark’, in which the beast is a lion and the girl must outwit the enchantress who cursed him, and ‘The White Stag’, in which the girl must undertake a series of seemingly impossible tasks to break the curse on her husband.

Sophie Hopmeier / Whilst most people know a handful of the most famous European fairy tales such as ‘Cinderella’, or ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, your new book focuses on lesser-known tales. How did you go about researching and selecting these stories, and why do you think they are important?

Kate Forsyth / There are just so many beautiful old stories, and it seems such a shame that so few people know them. I was also troubled by the fact that many people only knew the Disney version of a tale, when the original is so much darker and more powerful. Fairy tales are not just pretty amusing tales of magic and romance, they have a very important function as carriers of meaning and wisdom. I wanted to bring these old forgotten tales back to life, and help people discover tales that might move and enchant them.

Sophie Hopmeier / What ongoing role do you see fairy tales playing in contemporary life?

Kate Forsyth / As long as we have had language, we have been telling stories as a way to explore, illuminate and understand the human condition. Fairy tales are among the oldest and most enduring forms of storytelling, and their simplicity and vividness make them very memorable. This means they are more likely to survive and be passed down through the generations, while longer, more complicated stories are forgotten.

Fairy tales are often the first stories that children encounter, and so are the first time those children experience narrative transportation, the zen-like experience of being utterly immersed in a story. This absolute absorption in a story is the primary joy of narrative art, and it is addictive. Once we’ve been utterly entranced by one story, we want to have that feeling again and again.

Because fairy tales are narratives that cross the boundary of what is known into a realm where anything is possible, they help develop a vivid imagination and new ways of thinking. Ultimately this leads to creative problem-solving abilities and innovative thinking.

Fairy tales are also lesson tales — they teach us that there are right and wrong ways to behave, and that kindness will win out over cruelty, and courtesy over rudeness and selfishness.

Most importantly, I think, fairy tales offer us a stage in which to act out our anxieties, and to help us understand and manage our bewildering, complex human emotions. Fairy tales are full of dark, disturbing feelings — fear, envy, greed, grief, and lust — and it is a rare human who has not had to struggle to overcome such thoughts within themselves. So wonder tales help us deal with real-life situations within a safe and comforting environment, giving us the tools we need to navigate a world where the possibility of danger and harm is very real. Fairy tales are filled with joy, laughter, and wonder too, balancing out the darkness with light, and so they reassure us that, in time, the pain and suffering will end and all will be well. They give us hope, the greatest gift of all.

The ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition unfolds across three themed chapters. ‘Into the Woods’ explores the conventions and characters of traditional fairy tales alongside their contemporary retellings. ‘Through the Looking Glass’ brings together art, film and design that embrace exploratory stories of fantastical parallel worlds. ‘Ever After’ brings together classic and current tales to explore the many dimensions of love in all its complexities.

‘Beauty and the Beast’

Drawing on both the nineteenth-century picture book illustrations of Gustave Doré, and Surrealist cinema, Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (illustrated) has defined the public imagination of the 1757 story by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont for generations. When Belle (Josette Day) protects her father by agreeing to live with the monstrous Beast (Jean Marais), she gradually develops feelings for him. The extraordinary cinematography and effects of this sumptuous film heighten the striking subtext that one can love another not in spite of, but because of their difference.

The costume for ‘Adélaïde’, (one of Beauty’s (Belle’s) scheming sisters in Cocteau’s retelling), is one of the few remaining items from the 1946 film set still in existence (illustrated) on display in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition until 28 April 2024.

An enchanted red rose and a magic mirror (illustrated) also on display in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition are two key elements in the 2017 live action film Beauty and the Beast. These objects were drawn from the Walt Disney Studios remake, directed by Bill Condon, and were inspired by the well-known 1991 animation. The rose beneath a bell jar and the mirror resting on a table showcase the craftsmanship involved in bringing the fantastic world of fairy tales to life on screen.

Production stills from ‘La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast)’ (1946)

Production still from Beauty and the Beast 1946 / Director: Jean Cocteau / Image courtesy: British Film Institute / View full image

Production still from La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) 1946 / Director: Jean Cocteau / Image courtesy: Société nouvelle de distribution (SND) / View full image

La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) (1946) / 35mm, black and white, mono, 96 minutes, France, French (English subtitles) / Director/script: Jean Cocteau; Cinematographer: Henri Alekan; Editor: Claude Iberia / Cast: Jean Marais, Josette Day / Costume Designers: Antonio Castillo, Marcel Escoffier, Christian Bérard

Adélaïde’ costume ‘La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast)’ (1946) on display in ‘Fairy Tales’

Installation view ‘Fairy Tales’, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) Brisbane 2023 / Jean Cocteau (director), France 1889–1963; Film clip from La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) 1946; 35mm, black and white, mono, 96 minutes, France, French (English subtitles); Director/script: Jean Cocteau; Cinematographer: Henri Alekan; Editor: Claude Iberia; Cast: Jean Marais, Josette Day; Courtesy: Société nouvelle de distribution (SND), Paris; 1996–98 AccuSoft Inc. All Rights Reserved / Jean Cocteau (director), France 1889–1963; Marcel Escoffier (designer), Monaco 1910–2001; ‘Adélaïde’ costume from La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) 1946; Silk satin, wool cheesecloth, velvet, chiffon, straw; Collection: La Cinémathèque française, Paris; © Société nouvelle de distribution (SND); 1996–98 AccuSoft Inc. All Rights Reserved; Photograph: N Umek © QAGOMA / View full image

Production still from ‘Beauty and the Beast’ (2017)

Enchanted red rose under bell jar, and table from Beauty and the Beast 2017, Bill Condon (director), Sarah Greenwood (designer) / © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved / View full image

Rose in a bell jar, Mirror & Table on display in ‘Fairy Tales’

Bill Condon (director), United States; Sarah Greenwood (designer), England / From Beauty and the Beast 2017; Cast: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Luke Evans / / ‘Rose in a bell jar’; Glass, plastic, wire; 61 x 36 x 36cm / ‘Mirror’; Mirror, plastic, paint; 45.7 x 21.6 x 5cm / ‘Table’; Wood, marble, artificial snow, resin, plastic; 76.2 x 101.6 x 101.6cm / Courtesy: The Walt Disney Company / © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved / Photograph: N Umek © QAGOMA / View full image

The ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition is at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Australia from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

‘Fairy Tales Cinema: Truth, Power and Enchantment‘ presented in conjunction with GOMA’s blockbuster summer exhibition screens at the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

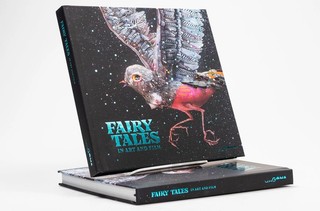

The major publication ‘Fairy Tales in Art and Film’ available at the QAGOMA Store and online explores how fairy tales have held our fascination for centuries through art and culture.

‘Fairy Tales’ merchandise available at the GOMA exhibition shop or online. / View full image

The Australian Cinémathèque

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) is the only Australian art gallery with purpose-built facilities dedicated to film and the moving image. The Australian Cinémathèque at GOMA provides an ongoing program of film and video that you’re unlikely to see elsewhere, offering a rich and diverse experience of the moving image, showcasing the work of influential filmmakers and international cinema, rare 35mm prints, recent restorations and silent films with live musical accompaniment by local musicians or on the Gallery’s Wurlitzer organ originally installed in Brisbane’s Regent Theatre in November 1929.

Dr Sophie Hopmeier is ‘Fairy Tales’ Assistant Curator and Assistant Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA