Minute beauty celebrated

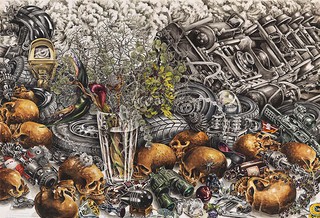

eX de Medici, Australia b.1959 / The theory of everything 2005 / Watercolour and metallic pigment on Arches paper / 114.3 x 176.3cm / Purchased 2005 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © eX de Medici / View full image

Over a career spanning almost forty years, eX de Medici has followed a range of artistic paths, while consistently critiquing the social and political systems that govern our lives. Having begun her career in the 1980s in painting, photomedia, performance and installation, de Medici worked for a decade as a tattooist after completing an apprenticeship in Los Angeles. She relinquished professional tattooing in 2000 to concentrate on watercolour, the medium for which she is best known.

De Medici’s dazzling, virtuosic watercolours foreground her central concerns, including the value and fragility of life, global affairs and the enmeshed and universal themes of power, conflict, and death. Her panoramic painting The wreckers 2019, for instance, decries global battles for political supremacy and their consequences. As the artist’s gallerist Joanna Strumpf has expressed, the work builds ‘on de Medici’s first depiction of a wreckage in Live the (Big Black) Dream 2006 (illustrated), which features a train crash and foreshadowed the Global Financial Crisis.’[24]

De Medici is also renowned for works of decorative art that are inspired by, and based on, her watercolours. Key examples include Shotgun Wedding Dress/ Cleave 2015 from the National Gallery of Australia, and The Seat of Love and Hate 2017–18, held by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.

Through these varied themes and materials, De Medici aims to seduce her viewers and shake them out of complacency. Ultimately, her audiences are as captivated by her aesthetic and technical brilliance, as they are by her topical and thought-provoking subject matter.

eX de Medici ‘Live the (Big Black) Dream’

eX de MEDICI, Australia b.1959 / Live the (Big Black) Dream 2006 / Watercolour and metallic pigment on paper / Purchased 2006. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery / © The artist / View full image

eX de Medici ‘The theory of everything’

eX de MEDICI, Australia b.1959 / The theory of everything 2005 / Watercolour and metallic pigment on Arches paper / Purchased 2005 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery / © The artist / View full image

Endnotes

- ^ Joanna Strumpf, ‘eX de Medici presents The Wreckers at Sullivan+Strumpf Sydney’, Art News Portal, 7 November 2019, https://www.artnewsportal.com/art-news/ex-de-medici-presents-the-wreckers-at-sullivan-strumpf-sydney.