Asia Pacific Triennial: New futures imagined

Subash Thebe Limbu, Yakthung people, Nepal/United Kingdom b.1981 / NINGWASUM (still, detail) 2020–21 / Single-channel video: 16:9, colour, sound, 40 minutes (approx.) / Purchased 2021. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Subash Thebe Limbu / View full image

QAGOMA’s landmark exhibition series, the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT), celebrates its tenth iteration in 2021. APT10 brings together more than 150 artists, collectives and filmmakers to reflect on complex histories, current urgencies and cultural encounters as they imagine a multiplicity of futures.

RELATED (Part 1): APT10: Navigating new futures

Ways of navigating and expressing our place in the world — and the influence of past encounters that hold meaning today — are embedded in objects, language, teaching and song throughout projects in APT10. For instance, the Air Canoe project focuses on the histories and cultures of the reefs, islands and waters that inform local art-making throughout the islands and atolls of northern Oceania, where understanding history relies on landscape and seascape literacy, and where navigational knowledge is an important aspect of cultural practice. Similarly, encounters over waterways become embedded in forms of art over time, such as knowledge of the winds, clouds and waters that underpinned exchange between voyagers from Macassar in Sulawesi to the beaches of north-east Arnhem Land. Sails, swords, paintings, pottery, performance and Larrakitj (memorial poles) have been gathered together from Indonesia, Arnhem Land and collections in Australia to illustrate these stories through the objects and materials influential in this pre-colonial history.

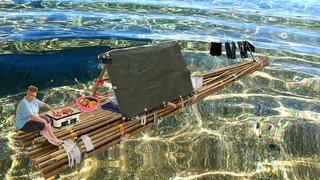

Salote Tawale, Fiji/Australia b.1976 / No Location (conceptual image) 2021 / Composite digital image / © and courtesy Salote Tawale / View full image

Edith Amituanai, Aotearoa New Zealand b.1980 / 501 tattoo (From ‘ La’u Pele Moana (My darling Moana)’ series) 2021 / Eco inks on 100% natural silk ed. 1/5 / 80 x 110cm / Purchased 2021 with funds from the Jennifer Taylor Bequest through the Queensland Art Gallery l Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery l Gallery of Modern Art / © and image courtesy Edith Amituanai / View full image

Pala Pothupitiye, Sri Lanka b.1972 / Kalutara Fort 2020-21 / Acrylic, ink and digital print on canvas / 123 x 157.5cm / Purchased 2021 with funds from Professor Emeritus Ian O’Connor AC and Anna Reynolds through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Pala Pothupitiye / View full image

Among some of the stories of journeys and migrations that have inspired works in APT10, artists investigate experiences in between cultures and places. Conceived to inhabit a fluid space between two lands, a reimagined bilibili (water vessel) by Salote Tawale (illustrated) holds a central position in GOMA’s long gallery. It takes the form of a 12-metre-long raft made from pliable lengths of bamboo lashed together with recycled bedsheets and rope. Similarly, a series of images created by Aotearoa New Zealand–based artist Edith Amituanai (illustrated) tell stories of unrequited aspirations of trans-Tasman travel, taking on new connotations during a time of unprecedented restriction. Elsewhere in the exhibition, artists challenge extant forms of mapping and impositions of colonial and military borders as lines of control. Pala Pothupitiye’s series (illustrated) of manipulated and crafted maps of Sri Lanka, along with Chong Kim Chiew’s installation of textured tarpaulin maps, seek to reclaim lands and cultures by interrogating the structures and histories that established boundaries of ownership, alluding to what Air Canoe co-curator Greg Dvorak describes as the ‘mythmaking of mapping’.[61] The ownership of land, the vulnerability of environments and the displacement of peoples are ideas that underpin contemporary art in the Asia Pacific region and are a palpable part of APT10.

Sumakshi Singh, India b.1980 / Installation view: ’33 Link Road’, Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, 2019 / © and image courtesy Sumakshi Singh / Photograph: Anil Rane / View full image

Maryam Ayeen, Iran b.1985 / Abbas Shahsavar, Iran b.1983 / Fall in dopamine (detail) 2020–21 / Gouache and watercolour / Seven works: six: 30 x 20cm (each); one:

190cm (diam., sheet) / Courtesy: The artists / © Maryam Ayeen and Abbas Shahsavar / View full image

Everyday lived spaces have become the source of narratives about social conditions and the imagination, in particular with experiences of domesticity assuming new meanings during the COVID-19 pandemic. APT10 constructs and gathers stories from these spaces, as architectures and homes instilled with memories and histories become both the subject and the form of projects in APT10. These include an installation of delicate threaded architecture by Indian artist Sumakshi Singh (illustrated), and a series of intimate and witty miniature paintings in which Iranian artists Maryam Ayeen and Abbas Shahsavar (illustrated)navigate the politics that preside over private and shared spaces through the confines of their domestic space in Tehran.

Engini (fire dance), Gaulim, January 2021 / Image

courtesy: Indigenous Uramat Identity / Photograph: Juan Lowe / View full image

Koji Ryui, Japan/Australia b.1976 / Citadel (installation detail) 2021 / Mixed media / Commissioned for ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10) / Courtesy: The artist and Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body, and Artspace, Sydney / © Koji Ryui / Photograph: N. Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

The varied materials, rituals and textures of the art-making of different locales is also fundamental to this exhibition, which seeks to engage with diverse contexts of cultural sharing and production. Working with the Uramat in Papua New Guinea, custodianship and the authority to view ceremonial objects outside their customary context has been called into question, while the community has been engaged to harness new ways for audiences to experience the objects in a dramatic multimedia installation. Conversely, Australian-based artists such as Koji Ryui (illustrated)and Brian Fuata explore relationships within the spaces of QAGOMA, reinterpreting and experimenting with the Gallery’s architecture, history, materiality and the presence of what cannot be seen. Invitations to step into cultural spaces are revealed and rationalised through other artworks in APT10: a Tongan fale (house made of local materials) by Seleka International Arts Society Initiative; the Balinese ritualised space of I Made Djirna’s installation; a deity-inhabited shrine by Vipoo Srivilasa; and immersive rainbow light representing safety for LGBTQI+ communities in Auckland‑based Shannon Novak’s gallery installation. Each space holds coded cultural connotations of the communities the work emerges from or engages with.

Collaborative, community-led ways of working are fundamental to the nature of many art-making contexts in the Asia Pacific region and hold a major presence in APT10 through a variety of rich and multi-faceted projects. Large groups working together in APT10 include artist collectives and communities as wideranging as the Bajau Sama Dilaut people in Sabah, Borneo; Gidree Bawlee Foundation of Arts in north-western Bangladesh; Seleka International Arts Society Initiative in Tonga; and the Kā Paroro o Haumumu: Coastal Flows / Coastal Incursions team from Aotearoa New Zealand. Other artists lead projects that rely on the participation of communities as producers of ambitious works, questioning the nature of representation and inclusivity while fostering agency for art-making communities for the future.

The artists and collaborators in APT10 draw on deep histories, current urgencies and cultural encounters — amicable and otherwise — that have shaped art and life across the Asia Pacific and which take on heightened relevance as we try to imagine a new future together.

Tarun Nagesh is Curatorial Manager, Asian and Pacific Art, QAGOMA;

Reuben Keehan is Curator, Contemporary Asian Art, QAGOMA; and

Ruth McDougall is Curator, Pacific Art, QAGOMA.

Part 2: This is an edited extract from the QAGOMA publication The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

RELATED (Part 1): APT10: Navigating new futures

Subash Thebe Limbu, Yakthung people, Nepal/United Kingdom b.1981 / NINGWASUM (still, detail) 2020–21 / Single-channel video: 16:9, colour, sound, 40 minutes (approx.) / Purchased 2021. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Subash Thebe Limbu / View full image

Endnotes

- ^ Greg Dvorak, Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll Between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 2018, p.37.