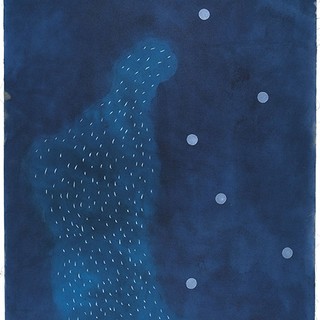

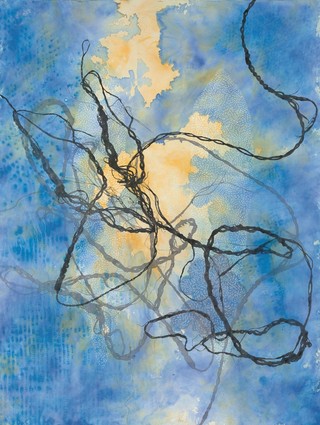

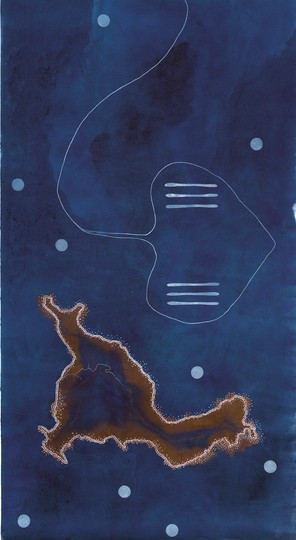

Judy Watson observes the advance of climate change in her painting moreton bay rivers, australian temperature chart, freshwater mussels, net, spectrogram 2022. A bird’s-eye view of Moreton Bay and its rivers are overlaid with a chart of Australia’s average air and water temperatures recorded between 1910 and 2019, tracking the increase in global warming.

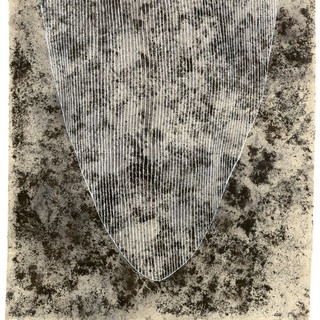

Watson integrated the scientific data alongside a spectrogram (a visual recording of sound) in which Aunty Helena Gulash spoke the Kabbi Kabbi/Gubbi Gubbi language word ‘gila’, meaning native bee (light coloured). With artist Tor MacLean, Watson experimented with botanically dyed materials at Maleny. Some of these contained iron filings from her nephew and Tor’s partner Dan Watson’s knife-making practice. Some of these works on fabric were hung from trees in the Maroochy Regional Bushland Botanic Gardens in a group exhibition, ‘Final Call’, as part of the Horizon Festival in 2021. The pieces were then dyed in an indigo vat at her cousin Dorothy Watson’s home near the flood-prone Oxley Creek in Brisbane. Later this work was overlaid with painted imagery that included the shadowed forms of three freshwater mussel shells, known as malu malu in Watson’s Waanyi language, with cross-hatched lines symbolising a net.

By carrying the residue of mapped Country, transforming the sound of breath into a spectrogram and plotting scientific charts, Watson reminds us of climate change’s existential threat in south‑east Queensland.

See more about the ‘Final Call’ exhibition.